Tracing Embodied Histories through the Waterways’ Memories of Tainan

hosted by “Absence Space” in Tainan,

co-organised by artists Craphone Liu, Kwan-Ying Chen, Shi-Min Sun, ShiYing Hu & Ting-Yung Chang,

supported by Tainan City Government Cultural Affairs Bureau

14 August - 1 September, 2025

Exploring Personal Embodied Histories, and Devising for Taiwan’s Public Space

Original Research Framework:

This particular proposal aims to introduce a research framework for a group of artists - ieke Trinks from Rotterdam, The Netherlands; CHEN 陳 GuanYing 冠穎 from Keelung City, Taiwan (R.O.C.), Dagmar I. Glausnitzer-Smith from Braunschweig, Germany, and HO 胡 WeiZen 偉仁, living in the Blue Mountains, Australia, to observe the points in which our embodied histories converge with the memory of place, as a means of shifting our performance-devising practices, particularly in public spaces. Artists Shih-Min Sun, Ting-Yung Chang, Naoto Yamagishi and Shi-Ying Hu were later invited to join this process.

Revealed through an increasing awareness of the interactive exchange between the histories residing in our bodies and the psycho-philosophical culture of place, the articulation of experience becoming ‘language’ emerges as an uncompromising commitment. This commitment leads us to interrogate and perhaps deconstruct the beliefs we often take for granted.

Central to this framework is the necessity to engage local artists who have personal ties to the city of Tainan, as our partnership is located at “Absence Space” in Tainan, who acted as our host. These artists’ intimate understanding of places enrich the depth of our inquiry and invigorates the dialogue surrounding our performances, ensuring a more profound resonance with the spaces we, as international artists, are temporarily occupying.

Empirical Objectives:

The research framework invites a dissolution of the conventional separations between process and presentation, allowing for the coexistence of varied approaches and fostering a greater probability for spontaneity. The visitation and interventions in public spaces, buildings, and environments occur alongside parallel, simultaneous performances and installation processes, reflecting on the boundaries of our perceived performance practices while cross-examining the socio-cultural layers embedded within public interactions.

Engaging with local communities and stakeholders is imperative to gather insights and perspectives on the sites to be explored. This can potentially be incorporated into a durational walking journey led by Tainan residents, which deepens the inquiry into place-responsive performative actions. Mediated through personal memories that intersect with collective history, these actions contribute to the development of an expanded performative vocabulary—through the transjective, which arises from the relatedness and co-creation between the observer and the world, and perhaps describes something that transcends the distinction between them.

Synopsis:

By delving into personal histories in connection to the history and memory of place, no matter how new or familiar, we hope to observe an unforeseeable relevance (or better relation), which may uncover different layers of meaning and understanding; revealed through an increasing awareness of our interactive exchange and between the histories residing in our bodies, and the psycho-philosophical culture of place.

Such a shift in perspective lays the groundwork for innovation in our performance-making process, allowing us to re-imagine spatial and compositional boundaries. This could lead to long durational performances that flow seamlessly from public spaces to internal Art Space buildings, creating dialogues that celebrate the organic connectivity between multiple dynamics and individual processes through solos, duets, and trios.

Dagmar’s Comment:

The work negotiates an incomprehensible complexity when surrounded by objects of sensory stimulation, and then the act of assuming intense attention on any one source can often be accomplished only with great difficulty. The preliminary ‘mountain’ as a metaphor is set in the ‘Arbeitsraum’ (workspace), which may be associated with a space in the mind. Here, gathered and collected objects are evaluated. They are like instrument collections in the orchestration of yet unexpected tunes. The infinitesimal focus is a crucial process which tends to present the ambiguity as to where the work begins and ends. It remains purposely unresolved - thus the potential for change and transition continues to take place.

The original concept of this proposal was conceived by WeiZen Ho, with Chinese translation by Faye Chen, 21/03/2025.

Kwan Ying CHEN then integrated this into his writing to seek funding from the Tainan local government; Integrated Concept of Kwan Ying CHEN and WeiZen HO, 30/3/2025

24 August 2025, the first all-group improvisation on a beach near Anping, in Tainan:

ieke Trinks, Dagmar I. Glausnitzer-Smith, Naoto Yamagishi, Kwan-Ying Chen, Craphone Liu, Shi-Ying Hu, Shih-Min Sun, Ting-Yung Chang and WeiZen Ho. Nick Kan was invited to improvise with the group.

24 August 2025, Performance response by Dagmar I. Glausnitzer-Smith, Anping Canal.

24 August 2025, Performance response to Tainan’s Spring Urban Lagoon. Shi-Min Sun and ieke Trinks were also responding performatively in the same location

Between the 10th-23rd August

Dagmar and I were the first of the international artists to arrive in Tainan, welcomed by Craphone Liu who outdid himself in familiarising us with the place of Tainan through its streets and varying food culture, the canals and up to its westernmost point of mainland Taiwan, the Guosheng Lighthouse below in the Cigu District of Tainan.

Much of our development began through gleaning for objects littered on the streets, blown by the wind, or set aside to be thrown out. The White Space was actually important for our installation-documentation process (see images below) to build towards the greater public space works. We had difficulty with Absence Space’s communal concept of space-sharing and the kind of flexibility required, even though we had specifically booked the space for our process; that other groups unrelated to our project could move our material-installation in-progress and even use it for their photographic shoot projects.

Performance Interventions, Lane 94, Section One, Beian Rd, Tainan

30 August 2025, Daliang Eco Park:

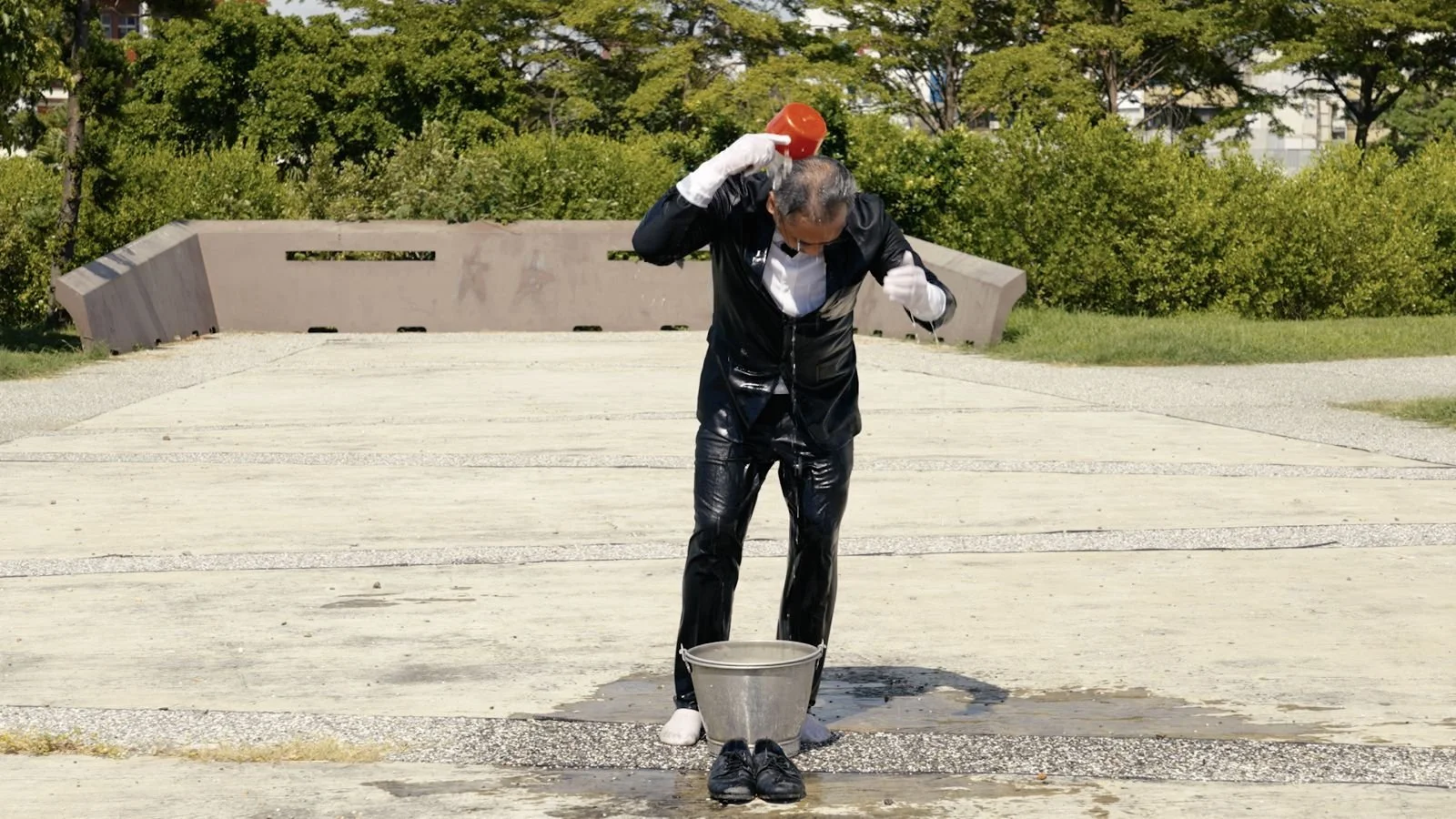

Water Traces - Craphone Liu’s performance response at Daliang Eco Park:

“ 在日正當中的炙熱時刻,我到公園旁台南運河汲取一桶水,然後將其澆灌於身著西裝的身體。濕透的衣料成為水的載體,當我倒地、摩擦、移動,身體在炙熱的公園地面留下一道道短暫的水痕。這些痕跡很快在烈陽下蒸發殆盡,彷彿歷史的殘影,稍縱即逝。

這個行為既是具體的身體書寫,也是道教儀式性的招喚——如同將水澆灌於路旁小廟,召集亡靈,將流動的運河歷史帶入當下。水的痕跡並非單純的殘留,而是靈性與記憶的顯影,既存在又消散。

〈水痕〉透過身體的濕度與地面的高溫,將歷史、宗教、肉身與自然力量交織為一場短暫的儀式。”

At the scorching height of noon, I drew a bucket of water from the Tainan Canal and poured it over my body clad in a formal suit. The soaked fabric became a vessel of water; as I collapsed, rubbed, and moved across the blistering ground of the park, my body inscribed fleeting traces of moisture. These marks quickly evaporated under the fierce sun—like spectral remnants of history, vanishing in an instant.

This act is both a concrete writing of the body and a Daoist invocation—akin to pouring water at a roadside shrine to summon wandering souls, channeling the flowing history of the canal into the present. The traces of water are not mere residues, but manifestations of spirit and memory, at once present and dissolving.

Through the dampness of the body and the heat of the ground, Water Traces entwines history, religion, the flesh, and the forces of nature into a ritual of transience.

Below are frame grab images from Jun-Kai Huang’s video documentation.

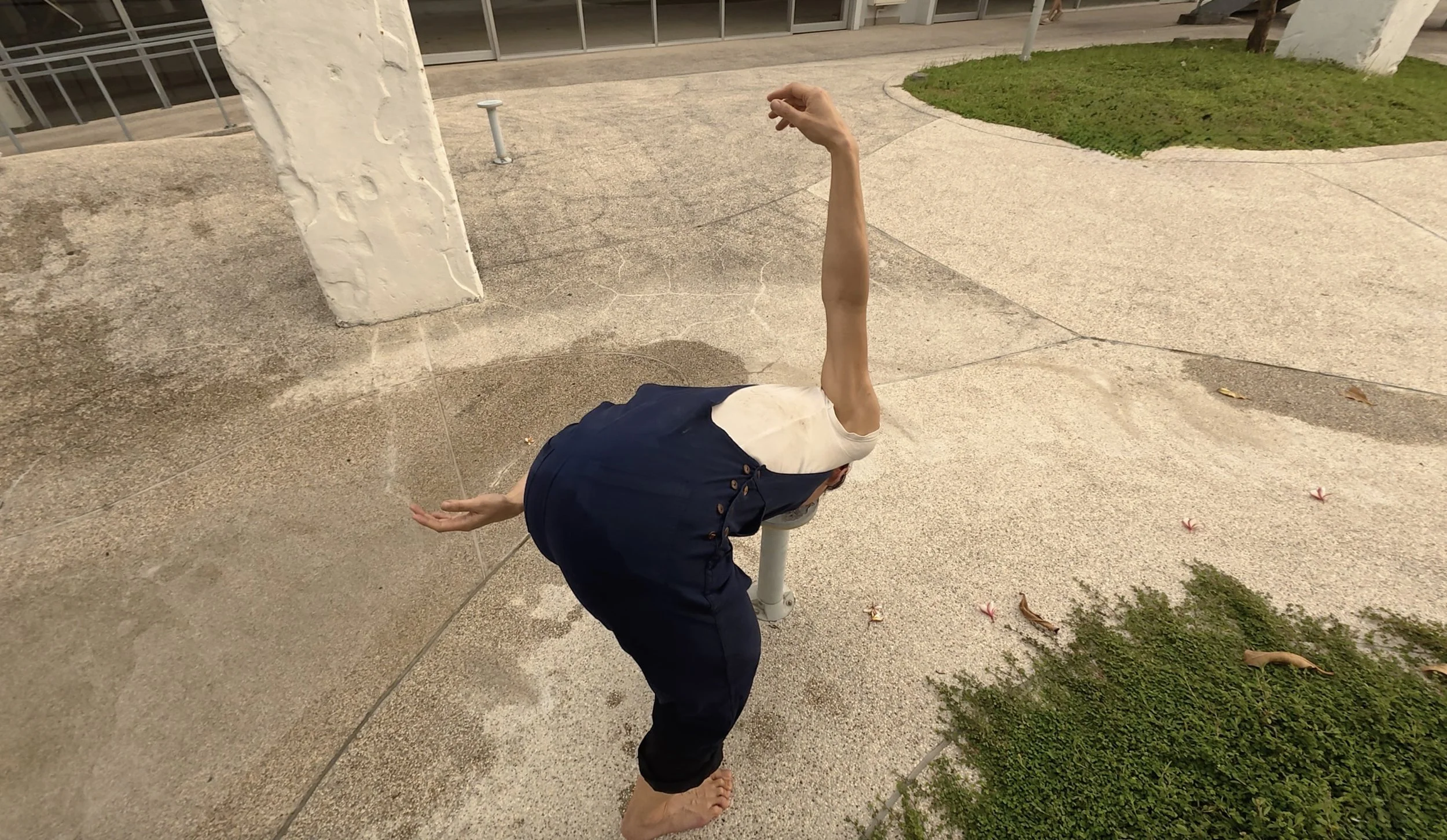

陳冠穎 Kuan-Ying Chen's and 張婷詠 Ting-Yung Chang’s performance response,

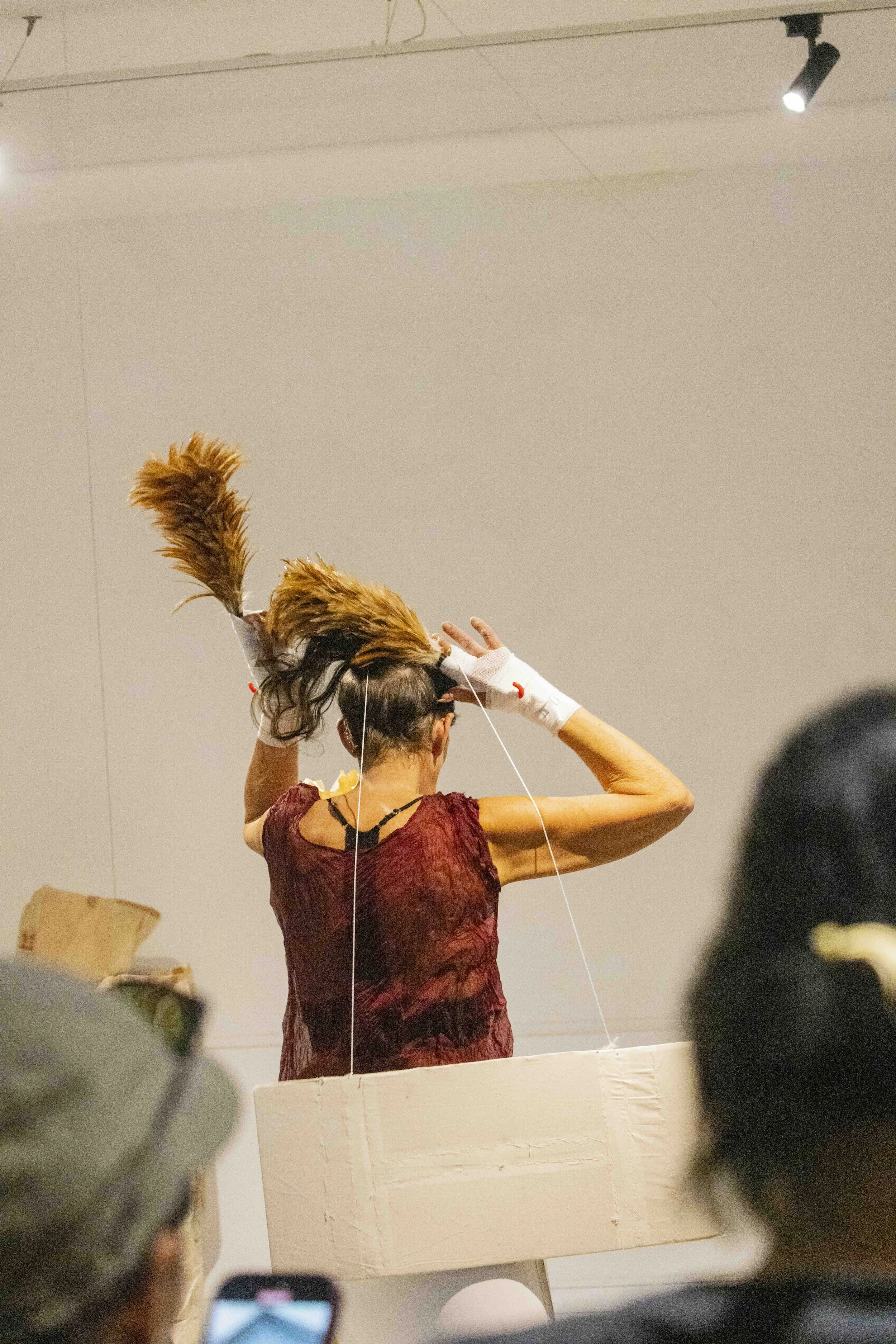

That evening, Dagmar I. Glausnitzer-Smith’s performance response, Spezi-Fish, Absence Space:

“Two dead fish were placed into the boxes prior to the performance.

A fish collected from the market is the infestation and as a host becomes a parasite in the white fabric material. The fish is completely alien to the surrounding place yet in another context so readily consumed and dealt with as natural sustenance.

The external space provides the source; the internal space (absent space, gallery space) is the place of transformation, where improbable animations of the objects in their creative form—images—can give further meaning as events and trigger a movement of thought/spirituality. That is, the illusion of movement as it transcribes itself into existence.

The wind must transpire.”

在表演之前,兩尾死魚被置入箱中。

一尾自市場取來的魚,化為侵蝕之象。作為寄主,它在白色布料的紋理之中轉化為寄生體。此魚對於現場顯得全然異質,然而在另一種語境下,它卻又作為日常的食物被消費、被吞嚥,被視為理所當然的自然養分。

外部空間提供源頭;內部空間(不存在之境、展演場域)則成為轉化之所。在此,物件以不可能的律動展現其創造性的姿態——成為影像——進而賦予事件更深層的意義,觸發思想與靈性的運動。換言之,運動的幻象在自我書寫的過程中,生成並確立為存在。

風必須滲透並發生。

31 August 2025, Absence Space and Chaitougang Creek:

Performance responses by Shih-Min Sun, Naoto Yamagishi, Shi-Ying Hu, ieke Trinks and WeiZen Ho. The performance/actions begin at Absence Space before the audience members are brought to the site of Chaitougang Creek.

My performance actions were intended to be the transitional vehicle: between ieke's question to people entering Absence Space, " what did your ancestors do for a living?", and how Naoto and Min could find a way of flowing in with their performance. The coffee ground was accumulated over two weeks from the owner of Mr More Coffee, the shells from an amazing Taiwanese hotpot, and the razor blade from a man round the corner whom Dagmar loves buying trinkets from. I am integrating the memories of my time with this micro-labour action, while listening to the answers most people gave. After which I change my attention and am responding more to the sounds that Naoto is evolving, wondering what Shih-Min is up to, watching Shi Ying riding on his yellow digger...

這是一種過渡的媒介行動:銜接了 Ieke 對進入「不存在空間」之人所提出的提問——「你的祖先以何為生?」——以及 Naoto 與 Min 如何在表演之中找到流入的方式。

咖啡渣來自兩週的積累,由 Mr More Coffee 的店主所提供;貝殼則源自一場奇妙的臺灣火鍋;剃刀片則來自街角一位 Dagmar 鍾愛購買小物的男子。

我在這些微小勞動的行動裡,將自身經驗的記憶逐步內嵌,並同時聆聽人們所給出的回應。隨後,我的注意力轉向另一種回應:傾聽 Naoto 所演化出的聲響,思索士閔正在醞釀什麼,凝望著仕穎駕駛著他的黃色挖土機……

ieke Trink’s notes on her performance response, Water Overtime:

“I spent one week in Tainan at Absence Space. On the map, I noticed nearby water and walked there one evening after the sun had already set. It turned out to be a different site than the one we had visited in the days before. The smell of the river was strong.

The next morning, together with Dagmar I. Glausnitzer-Smith and WeiZen Ho—fellow international participating artists in the project, alongside local artists—I returned to the site. Along the river we discovered some community gardens, while from the opposite side rhythmic industrial sounds set Dagmar into a repetitive movement. Despite the toxic smell, fish still leapt from the water. We were all intrigued by the site and felt compelled to return. On the one hand it was uninviting—harsh and polluted—yet on the other, it seemed to lure us in, inviting us to encounter and explore its hidden layers.

The river was called Chaitougang Creek. In earlier times it had been vital to the surrounding farmland. Land and waterways in Tainan have shifted over time, reshaped by typhoons that displaced or erased rivers. To reach the creek, one had to pass through tall grass growing on its banks.

Earlier in the week, Craphone—also a participating artist and our host in Tainan—had taken us to the seashore. There, I found two empty plastic bottles that had washed ashore, one labeled from China and the other from Vietnam. For my action, I brought these bottles with me to Chaitougang Creek. At the creek, I filled one with its water and then poured it into the other, each time placing the empty bottle a few steps ahead. In this way, the water slowly walked through the city, from one bottle to the other, as if the bottles were its shoes and the creek itself was moving through Tainan.

This action is connected to Fluxus performance traditions, in particular Tomas Schmit’s Zyklus für Wassereimer, performed on December 18, 1963 in Amsterdam. In it, Schmit poured water from one milk bottle to another arranged in a circle until all the water was spilled, transforming a simple everyday gesture into a durational performance where repetition itself became the work. My own action, performed on September 30, 2025 in Tainan as part of Tracing Embodied Histories Through the Waterways of Tainan, echoed this gesture of pouring, but placed it in dialogue with a specific body of water—polluted, fragile, and in need of care—carried step by step into public space.

In the past, the relationship with water and this creek must have been strong, sustaining food production, irrigation, and transportation—until it was reduced to a drainage channel. Today, people, including artists and environmentalists, are fighting for the creek, hoping to restore its vitality and make the water clean again.

The water I carried I cherished. Only a few drops spilled on the roadside as I made my way back to Absence Space.”

Opposite ieke’s Water Overtime, WeiZen has begun her hour-long performance utilising blue silk cloth, blue threads at the footbridge in front of the public utility dam of Chaitougang Creek; this creek lies between the farmland, factories and ocean:

“Two found branches in the area are bound by black cotton twine into one longer branch, and attached to the steel fence of the footbridge. Three spools of blue thread are inserted onto the branch. Dried branches are laid onto the floor of the footbridge and a blue silk fabric is layered over them. I begin by gently pulling three threads from each spool and twining them around the upper half of my body. I keep up this action of pulling and twining until the threads get caught and I start over again. Sometimes I keep up a rhythm and sometimes the threads get tangled. I stop to untangle the threads and attempt to start over. How the threads snag and flow forms my body’s geometry, positioning and movement. Like the water, I flow and I stagnate when caught and trapped. Like a fish I swim and I get entangled. I attempt to sense the energy of water; how it is at once so evident, so unifyingly one body. As soon as we dip into it we are also one body with it, connected to everything water is a part of. Water is also invisible; how it is absorbed into every crevice, be it stone or parched soil; how it evaporates and how it forms clouds. And in all of its capacity to sustain life, it also destroys in its violence and overwhelming enormity. As water breaks things apart, water holds what is thrown into it. Water purges and belches out the entanglement of objects as it swirls them in its belly. Water always reminds us what we have given it. The memory of water is seen and not seen, it moves people and facilitates trade, exchange and conquering forces. Water moves beneath our feet even as we place layers of concrete over it and struggle to contain this element in pipes and dams. These qualities of water, I attempt to connect with.”

在現場撿到的兩根樹枝,被以黑色棉線綑綁為一體,形成更長的枝桿,並固定於人行橋的鋼製圍欄。枝桿上插入了三卷藍線。乾枯的枝條鋪設於橋面的地板上,其上覆蓋一層藍色絲布。

我以溫和的手勢,從每一卷線中抽出三股絲線,纏繞於身體的上半部。我持續進行這個抽取與纏繞的行動,直到線被卡住,再重新開始。有時候我維持著某種節奏,有時則陷入糾結。我停下來解開線結,然後再度開始。絲線如何被勾住或流動,塑造了身體的幾何、位置與動作。正如水流,我在暢行與停滯之間被牽制;正如魚群,我在游動與糾纏之間徘徊。

我嘗試感知水的能量:它顯而易見,卻又在統一之中成為一體。我們一旦浸入其中,便與之同體,與水所連繫的一切相互銜接。水同時也是不可見的:它滲入石縫或乾渴的泥土,它蒸散、化為雲朵。它在孕養生命的同時,也以暴烈與龐大摧毀。水能分解事物,亦能承載拋擲其中的一切;水在翻湧的腹腔裡消化並排出糾纏的物件。水總提醒我們,曾賦予它什麼。水的記憶既可見又不可見,它推動人群,促進貿易、交換與征服的力量。即使我們以混凝土層層覆蓋,或以管道與水壩試圖限制,水依然在我們腳下流動。

我試圖與這些水的特質產生連結。

Behind the walls of the dam, Naoto Yamagishi begins his contemplative performance response, Forgotten Grass:

“忘却の川をなぞる。

ただ確かにそこに在る音を、静寂を、不在の在を、

共演者と記憶の層と重ね合わせまだ見ぬ風景を立ち上げた。”

Tracing the river of oblivion.

The sound, the silence,

the being of absence itself certainly there,

layered with fellow performers and the strata of memory,

we brought forth a landscape yet unseen.

描摹遺忘之川。

只是在那確然存在的聲響、靜寂,以及不在的在之中,

與共演者、與記憶的層疊相互交織,

一幅尚未被看見的風景因而被喚起。

Naoto moves closer to where Shih-Min SUN’s performance titled, Windowsill, takes place:

“走在城市的舊水道之間,我以炭色的臉注視水道;我希望再現自身、母親及祖母的視角所見的最早河道、運河與煤炭,來來往往,跨越史前時代、今時與明日的景象。

(附註):

在藝術領域中,對我影響深遠的女性與資深前輩,以美學知識與指導支持我,本作亦作為對他們啟發的致意。本作品之構思與執行均由本人獨立負責,若引發任何爭議或法律責任,概由本人承擔,與主辦單位、策展人及合作藝術家無涉。未能於事前逐一告知策展人,深表歉意,並感謝各方的理解與支持。”

Shih-Min’s notes in English on Windowsill:

Walking among the old waterways of the city, I observe the water with a face marked in charcoal; I hope to reenact the earliest rivers, canals, and coal as seen from the perspectives of myself, my mother, and my grandmother, flowing back and forth across prehistoric times, the present, and the future.

Note: Within the field of art, women and senior predecessors who have profoundly influenced me have supported me with their aesthetic knowledge and guidance. This work can also be regarded as a tribute to the inspiration they have provided.

This work was conceived and executed solely under my responsibility. I bear full liability for any disputes or legal issues, with no involvement of the organizers, curators, or collaborating artists. I apologize for not informing each curator in advance and sincerely thank everyone for their understanding and support.

Amidst the unfolding events, ShiYing Hu guides his yellow digger from the street onto the long grass, echoing ieke’s performance presence as he steadily trundles toward Chaitougang Creek.

Naoto’s coils from the slinky become entangled with the blue threads…

…time to walk back towards Absence Space…

Thank you to all the amazing artists and the witnesses who passed us, came closer and stayed. I have only been able to show part of the works we have created; there was so much more!

Afterword, upon reflection

To create a participatory performance work that explores the connections and intersections between embodied histories and the memories that places hold, we need to adopt a multi-phase methodological frameworks that integrate concepts from memory studies, embodied practices, and participatory art. The unresolvable issue I believe, is how the notion of history and memory is conflated in our minds, and how we can use these processes to probe and clarify the moments of slippages for ourselves. Some key methodological frameworks and questions to consider (which may be used in different combinations) are:

Embodied Memory and Performance-Based Methods:

This project phase highlights the potential of performance-based methods to explore embodied memories. Performance, as a physical and social activity, can serve as a medium for creating, questioning, and negotiating shared pasts. This approach emphasises the body as a site of memory and a tool for integrating and allowing lived experiences to be take on open forms physical and material externalisations.

Framework: Use physical action and movement expression as a primary method to access and communicate embodied histories and memories.. This can involve improvisation, and body-material-image response experiments to the term ‘history’ and ‘memory’.

Interplay of History and Memory:

This part of the process would attempt to distinguish between history (a reasoned reconstruction of the past) and memory (a sacred, emotional connection to the past). It emphasises the importance of understanding the interplay between these concepts and their socio-political implications.

Framework: Incorporate historical research alongside personal and collective memory work, exploring how these narratives intersect, conflict, and shape identity and culture.

Speculative Processes:

Speculation is proposed as a method for imagining alternative futures and framing artistic work. This involves creating performative experiments that challenge dominant narratives and explore uncertainty.

Framework: Design speculative exercises that encourage participants to imagine and enact alternative ways of relating to their embodied histories and the memories of places.

Syncretism and Multiplicity:

Using syncretism as a principle for bringing together diverse perspectives, histories, and values. This approach allows for the coexistence of contradictions and multiplicities, fostering dialogue and exploration which move between conversations and actions

Framework: Create spaces for participants to share their personal histories and perspectives, encouraging the coexistence of diverse narratives and fostering collaborative creation; that when a contradictory view is expressed, this does not ‘delete’ the other views. Instead, we could commit to creating a space to include all these views in a series of discourse.

Participatory and Descriptive Anthropology Approaches:

An anthropologist could be invited to collaborate to brainstorm participant observation methods for understanding embodied memories, emphasizing the importance of lived practices and social interactions.

Framework: Engage participants in co-creation processes, using interviews, storytelling, and collaborative workshops to explore their embodied histories and the memories associated with specific places.

So many questions…

Understanding Embodied Histories:

How do participants experience and express their personal histories through their bodies? How are they different from memories in bodies?

What physical movements, gestures, or practices are associated with specific memories or historical events?

Exploring Place-Based Memories:

What memories do participants associate with specific places, and how do these places shape their sense of identity and history?

How do the physical and social environments of these places influence the embodied experiences of memory? Can place itself, have memories?

Intersections of History and Memory:

How do participants perceive the relationship between their personal memories and broader historical narratives?

Are there tensions or alignments between individual and collective memories of a place?

Multiplicity and Contradictions:

How can the performance work create a space for multiple, contradictory perspectives to coexist and interact?

What strategies can be used to navigate disagreements and foster meaningful dialogue among participants?

Speculative and Creative Processes:

How can speculative methods be used to imagine alternative ways of understanding and relating to embodied histories and place-based memories?

What role can artistic experimentation play in revealing new insights about the connections between body, history, and place?

Ethical and Social Considerations:

How can the participatory process ensure inclusivity and respect for diverse experiences and perspectives?

What ethical considerations should be addressed when working with personal and collective memories?